The introduction of genome sequencing and other molecular techniques has been increasingly used to determine phylogenetic relatedness of microorganisms. This has led to an explosion of novel microbial taxonomy.

Prior classification criteria such as phenotypic characteristics have demonstrated to be insufficient and sometimes misleading when classifying organisms within different families, genera, or species.

Although the clinical utility of many of the new taxonomy revisions remain to be seen, the accurate identification of organisms is important in the understanding of pathogenesis and epidemiology of infections and it can have an impact on the antibiotic susceptibility testing and data interpretation.

Trying to keep up with all these changes can be a daunting experience for the microbiology laboratory; on the other hand, it is important that the laboratory remains current and clinically relevant.

In 2013, CMPT sent a Paper Challenge on this topic, to discuss the proper procedure for the laboratory to incorporate new nomenclature into their reporting practices.

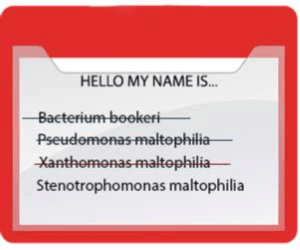

The discussion mentioned that for some clinicians, the microbial terminology that they are familiar with is the terminology they prefer, while for others, the new terminology, once established in literature, becomes their first choice so the clinical laboratory needs to meet the needs of both groups.

In an opinion expressed within the Manual of Clinical Microbiology (American Society for Microbiology), the preferred alternative is to present both the old and the new name within the same report for some period, or at least until the path forward becomes clear.

“When laboratories adopt taxonomic changes, the older epithet should be included in parentheses following the new name for a minimum of 6 months. For infrequently encountered pathogenic organisms, 6 months may be insufficient for physicians to become familiar with the taxonomic change. It is the laboratory’s responsibility to ensure that clinicians are aware of the significance of the organism being reported in these cases.”

At some point it may be that the new name has become so well established in both literature and clinical practice, that using two names is no longer necessary or appropriate. Perhaps the most problematic outcome is when different laboratories in a geographic region make differing decisions, with some laboratories adapting change and others electing to not.

Responding to an increasing need to summarize new clinically important organisms and changes in the nomenclature and classification of known organisms, the Journal of Clinical Microbiology has committed to write updates every two years on these changes.

The first series of minireviews were published in January 2017 and the second were published in February 2019.

Below, we summarize some of the changes that affect commonly seen organisms in the clinical microbiology laboratory. For more comprehensive lists and newly described organisms please check the references.

BACTERIA

One of the most significant changes has been the reorganization of families and genera within what is now known as Enterobacteriales. In brief, the Enterobacteriaceae family has been divided into seven families:

Erwiniaceae – containing the genera Erwinia, Buchnera, Pantoea, Phaseolibacter, Tatumella, and Wigglesworthia.

Pectobacteriaceae: containing the genera Pectobacterium, Brenneria, Dickeya, Lonsdalea, and Sodalis

Yersiniaceae: containing the genera Yersinia, Chania, Ewingela, Tahnella, Rouxiella, Samsonia, and Serratia.

Hafniaceae: containing the genera Hafnia, Edwardsiella, and Obesumbacterium.

Morganellaceae: containing the genera Morganella, Arsenophonus, Cosenzaea, Moellerella, Photorhabdus, Proteus, Providencia, and Xenorhabdus.

Budviciaceae: containing the genera Budvicia, Leminorella, and Pragia

Enterobacteriaceae: containing the remaining Enterobacteriales genera.

Enterobacter aerogenes has now been transferred to Klebsiella aerogenes. Although the clinical utility of this change remains to be seen, the change in taxonomy may bring confusion to clinicians as Klebsiella and Enterobacter genera are usually identified with different patters of antimicrobial susceptibility.

Species of the genus Propionibacterium associated with human skin have now been placed in a new genus: Cutibacterium, which includes the species Cutibacterium acnes, C. avidum, and C. granulosum; formerly Propionibacterium propionicum is now Pseudopropionibacterium propionicum.

The genus Clostridium has also undergone extensive revision. This genus has been reserved now for Clostridium butyricum while the rest of the species will be assigned to new genera. Clostridium difficile has now been assigned to the new genus Clostridioides thus the new designation Clostridioides difficile.

FUNGI

Historically, sexual and asexual forms of the same fungi species were given different names. However, molecular methods have allowed to confirm that these separate forms belong to the same species making the different names redundant.

As of January 2013, the dual-naming system is no longer permitted by the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants.

This concept together with new molecular phylogenetic analysis will lead to significant changes in naming and classification of fungi.

Proposals for name changing and re-classification have been evaluated for the genus Cryptococcus, dermatophytes, Blastomyces, Paracoccidioides, and Sporothrix, among others.

PARASITES

Parasites have long been classified by morphological characteristics; following the trend in bacteriology and mycology, current classifications schemes are likely to evolve in the coming years.

Balantidium coli has now been reclassified as Neobalantidium coli to accommodate Balantidium species with warm-blooded hosts.

Diphyllobothrium species associated with human disease have been classified into two genera: Adenocephalus and Dibothriocephalus. The genus Diphyllobothrium has been reserved for cetacean (whale) parasites.

The genus Adenocephalus accommodates the previously named Diphyllobothrium pacificum while the genus Dibothriocephalus accommodates the species D. latum, D. nihonkaiense, D. dendriticum, D. dalliae, and D. ursi.

It is important to note that these changes in taxonomy do not have any clinical implications.

CONCLUSIONS

With the explosion of molecular techniques classification of microorganisms has undergone major changes. Phenotypic characteristics have shown not sufficient to classify and group organisms and thus, new group of bacteria, fungi, and parasites are being recognized and presented.

The new classifications may bring more understanding on the epidemiology, pathogenicity, and antimicrobial susceptibility of the organisms.

Caution however should be taken in reporting new or revised organisms to the clinician without the proper education or understanding of what the changes if any these new species or names may bring to the treatment of the patient.

It is the laboratory’s responsibility to ensure that clinicians are aware of the significance of the organism being reported in these cases.

REFERENCES

1. Kraft CS, McAdam AJ, Carroll KC. A Rose by Any Other Name: Practical Updates on Microbial Nomenclature for Clinical Microbiology. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;55:3-4.

2. Munson E, Carroll KC. What’s in a Name? New Bacterial Species and Changes to Taxonomic Status from 2012 through 2015. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;55:24-42.

3. Munson E, Carroll KC. An Update on the Novel Genera and Species and Revised Taxonomic Status of Bacterial Organisms Described in 2016 and 2017. J Clin Microbiol. 2019;57:10.1128/JCM.01181-18. Print 2019 Feb.

4. Warnock DW. Name Changes for Fungi of Medical Importance, 2012 to 2015. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;55:53-59.

5. Warnock DW. Name Changes for Fungi of Medical Importance, 2016-2017. J Clin Microbiol. 2019;57:10.1128/JCM.01183-18. Print 2019 Feb.

6. Simner PJ. Medical Parasitology Taxonomy Update: January 2012 to December 2015. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;55:43-47.

7. Mathison BA, Pritt BS. Medical Parasitology Taxonomy Update, 2016-2017. J Clin Microbiol. 2019;57:10.1128/JCM.01067-18. Print 2019 Feb.